Rational Roots and Synthetic Division

The rational roots theorem can help us find zeros of polynomials without blindly guessing.

This post is part of the book Justin Math: Algebra. Suggested citation: Skycak, J. (2018). Rational Roots and Synthetic Division. In Justin Math: Algebra. https://justinmath.com/rational-roots-and-synthetic-division/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

In the previous post, we learned how to find the remaining zeros of a polynomial if we are given some zeros to start with. But how do we get those initial zeros in the first place, if they’re not given to us and aren’t obvious from the equation?

Rational Roots Theorem

The rational roots theorem can help us find some initial zeros without blindly guessing. It states that for a polynomial with integer coefficients, any rational number (i.e. any integer or fraction) that is a root (i.e. zero) of the polynomial can be written as some factor of the constant coefficient, divided by some factor of the leading coefficient.

For example, if the polynomial $p(x)=2x^4+x^3-7x^2-3x+3$ has a rational root, then it is some positive or negative fraction having numerator $1$ or $3$ and denominator $1$ or $2$.

The possible roots are then $\pm \frac{1}{2}$, $\pm 1$, $\pm \frac{3}{2}$, or $\pm 3$. We test each of them below.

We see that $x=\frac{1}{2}$ and $x=-1$ are indeed zeros of the polynomial.

Therefore, the polynomial can be written as

for some constants $b$ and $c$, which we can find by expanding and matching up coefficients.

We find that $b=0$ and $c=-6$.

The remaining quadratic factor becomes $2x^2-6$, which has zeros $x=\pm \sqrt{3}$.

Thus, the zeros of the polynomial are $-\sqrt{3}$, $-1$, $\frac{1}{2}$, and $\sqrt{3}$.

Synthetic Division

To speed up the process of finding the zeros of a polynomial, we can use synthetic division to test possible zeros and update the polynomial’s factored form and rational roots possibilities each time we find a new zero.

Given the polynomial $x^4+3x^3-5x^2-21x-14$, the rational roots possibilities are $\pm 1$, $\pm 2$, $\pm 7$, and $\pm 14$.

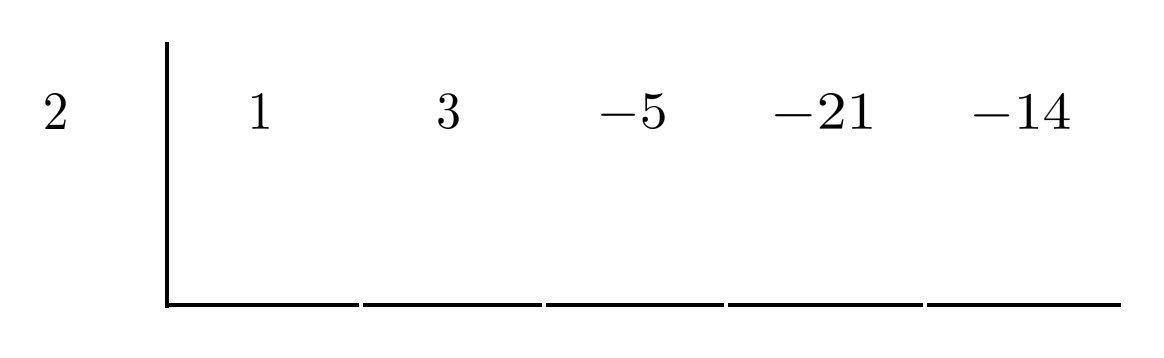

To test whether, say, $2$ is a zero, we can start by setting up a synthetic division template which includes $2$ at the far left, followed by the coefficients of the polynomial (in the order that they appear in standard form).

We put a $0$ under the first coefficient (in this case, $1$) and add down the column.

Then, we multiply the result by the leftmost number (in this case, $2$) and put it under the next coefficient (in this case, $3$).

We repeat the same process over and over until we finish the final column.

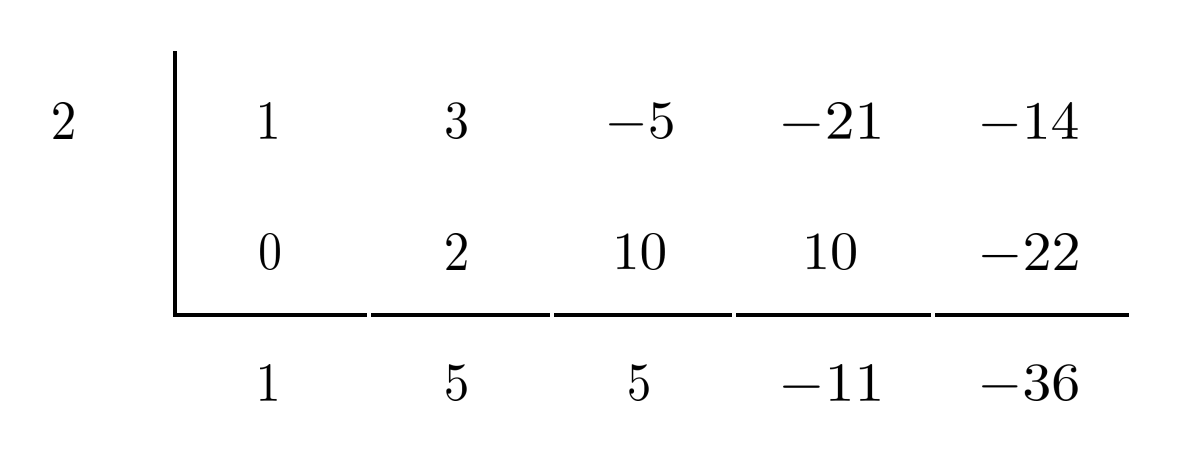

The bottom-right number is the remainder when we divide the polynomial by the factor corresponding to the zero being tested. Therefore, if the bottom-right number is $0$, then the top-left number is indeed a zero of the polynomial, because its corresponding factor is indeed a factor of the polynomial.

In this case, though, the bottom-right number is not $0$ but $-36$, so $2$ is NOT a zero of the polynomial.

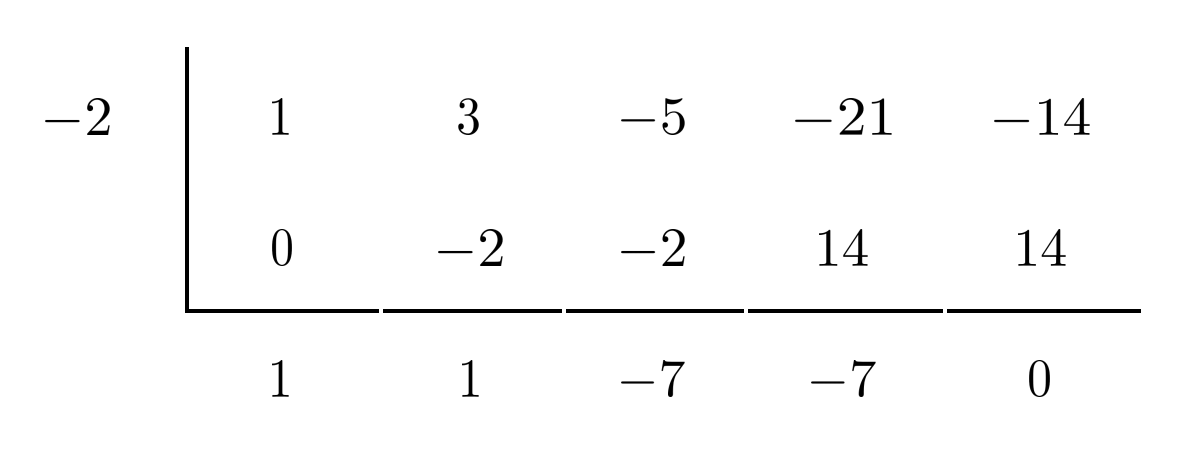

However, when we repeat synthetic division with $-2$, the bottom-right number comes out to $0$ and we conclude that $-2$ is a zero of the polynomial.

Then $x+2$ is a factor of the polynomial, and the bottom row gives us the coefficients in the sub-polynomial that multiplies to yield the original polynomial.

The next factor will come from $x^3+x^2-7x-7$, so the rational roots possibilities are just $\pm 1$ and $\pm 7$.

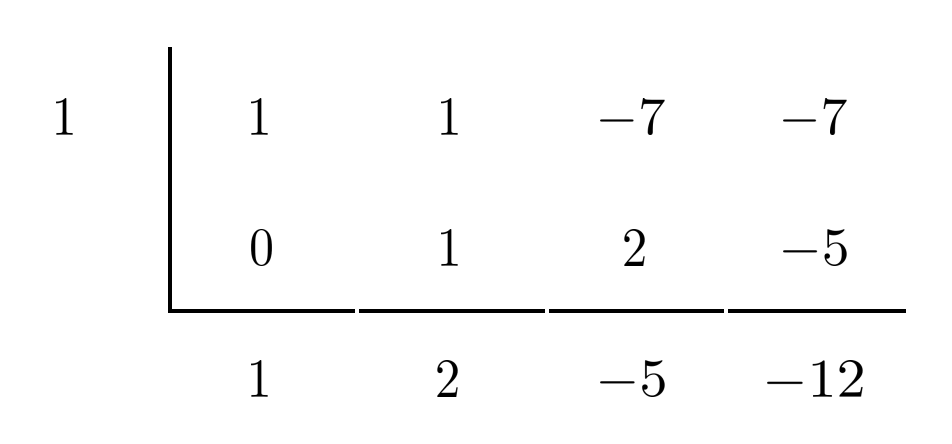

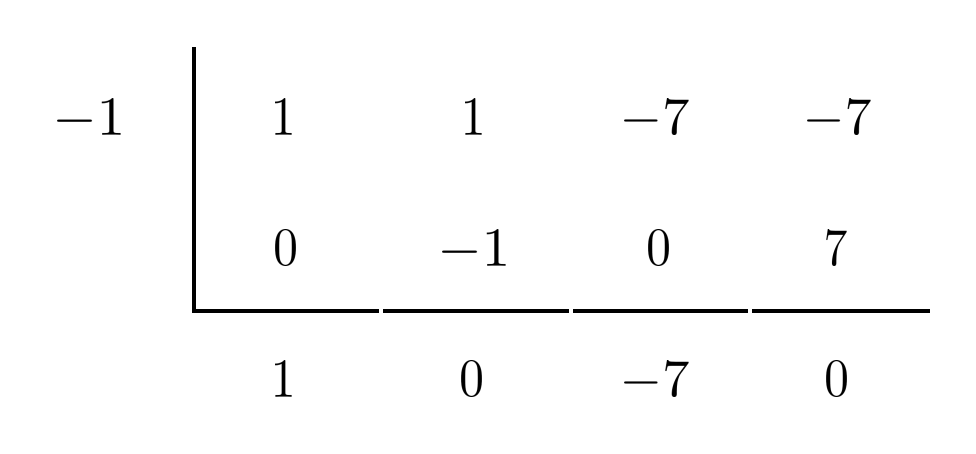

We use synthetic division to test whether $x=1$ is a zero of $x^3+x^2-7x-7$.

Since the bottom-right number is $-12$ rather than $0$, we see that $x=1$ is not a zero of $x^3+x^2-7x-7$. However, $x=-1$ is!

Using the bottom row as coefficients, we update the factored form of our polynomial.

Now that we’re down to a quadratic, we can solve it directly.

Thus, the zeros of the polynomial are $-2$, $-1$, $\sqrt{7}$, and $-\sqrt{7}$, and the factored form of the polynomial is

Final Remarks

In this example, the polynomial factored fully into linear factors. However, if the last factor were $x^2+7$, which does not have any zeros, we would leave it in quadratic form. The zeros of the polynomial would be just $-2$ and $-1$, and the fully factored form of the polynomial would be $(x+2)(x+1)(x^2+7)$.

One last thing about synthetic division: be sure to include ALL coefficients of the original polynomial in the top row of the synthetic division setup, even if they are $0$. For example, the polynomial $3x^4+2x$ is really $3x^4+0x^3+0x^2+2x+0$, so the top row in the synthetic division setup should read $\hspace{.5cm} 3 \hspace{.5cm} 0 \hspace{.5cm} 0 \hspace{.5cm} 2 \hspace{.5cm} 0$.

Exercises

For each polynomial, find all the zeros and write the polynomial in factored form. (You can view the solution by clicking on the problem.)

$1) \hspace{.5cm} 3x^3+18x^2+33x+18$

Solution:

$3(x+1)(x+2)(x+3)$

$\text{zeros: } -1, -2, -3$

$2) \hspace{.5cm} 2x^3-5x^2-4x+3$

Solution:

$(2x-1)(x+1)(x-3)$

$\text{zeros: } \frac{1}{2}, -1, 3$

$3) \hspace{.5cm} x^4-4x^3+3x^2+4x-4$

Solution:

$(x+1)(x-1)(x-2)^2$

$\text{zeros: } \pm 1, 2$

$4) \hspace{.5cm} x^4-3x^3+5x^2-9x+6$

Solution:

$(x^2+3)(x-2)(x-2)$

$\text{zeros: } 1, 2$

$5) \hspace{.5cm} x^4-2x^3-x^2+4x-2$

Solution:

$(x-1)^2(x+\sqrt{2})(x-\sqrt{2})$

$\text{zeros: } 1, \pm \sqrt{2}$

$6) \hspace{.5cm} 2x^4+7x^3+6x^2-x-2$

Solution:

$(2x-1)(x+2)(x+1)^2$

$\text{zeros: } \frac{1}{2}, -2, -1$

$7) \hspace{.5cm} 2x^4-8x^3+10x^2-16x+12$

Solution:

$2(x-1)(x-3)(x^2+2)$

$\text{zeros: } 1, 3$

$8) \hspace{.5cm} 21x^5+16x^4-74x^3-61x^2-40x-12$

Solution:

$(x+2)(x-2)(7x+3)(3x^2+x+1)$

$\text{zeros: } \pm 2, -\frac{3}{7}$

This post is part of the book Justin Math: Algebra. Suggested citation: Skycak, J. (2018). Rational Roots and Synthetic Division. In Justin Math: Algebra. https://justinmath.com/rational-roots-and-synthetic-division/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.