Cognitive Science of Learning: Minimizing Associative Interference

Associative interference occurs when related knowledge interferes with recall. It is more likely to occur when highly related pieces of knowledge are learned simultaneously or in close succession. However, the effects of interference can be mitigated by teaching dissimilar concepts simultaneously and spacing out related pieces of knowledge over time.

This post is part of the book The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Jan 2024). Suggested citation: Skycak, J., advised by Roberts, J. (2024). Cognitive Science of Learning: Minimizing Associative Interference. In The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Jan 2024). https://justinmath.com/cognitive-science-of-learning-minimizing-associative-interference/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.

Associative interference describes the phenomenon that conceptually related pieces of knowledge can interfere with each other’s recall. For instance, it is easy to mistake a leopard for a cheetah.

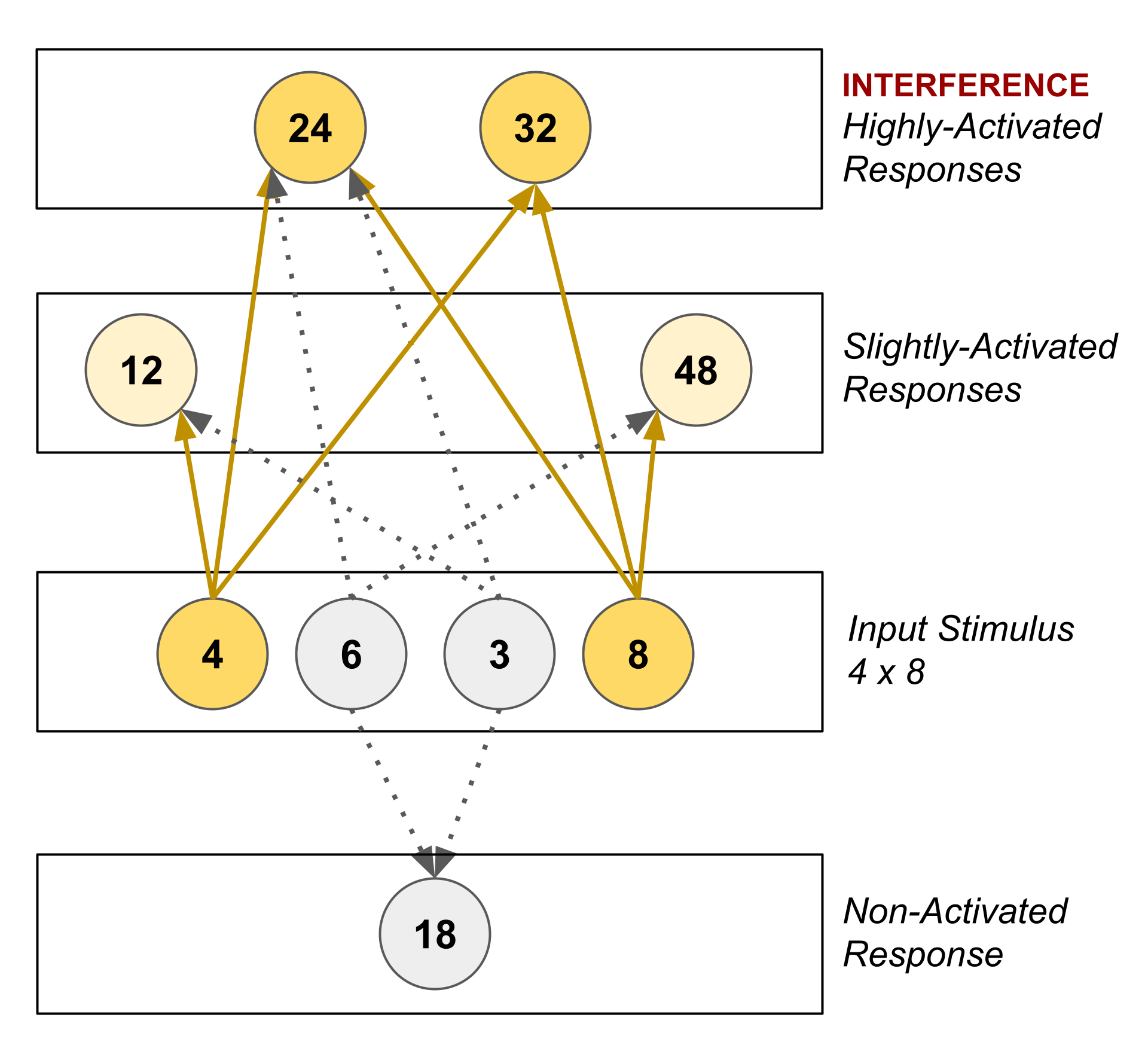

The same happens in math. Multiple studies have shown that well over half, and potentially as high as 90%, of multiplication mistakes are caused by interference (see Campbell, 1987 for a summary). For instance, when recalling 4 × 8, related facts like 4 × 6 = 24 and 3 × 8 = 24 interfere with the spreading activation during the recall process and increase the likelihood of the error 4 × 8 = 24. (This phenomenon occurs throughout math – multiplication facts are just a convenient setting for academic studies.)

Non-Interference

While it is not possible for a teacher to change the structure of knowledge to make different pieces of information less related, further research in interference theory has revealed a factor that can be controlled by a teacher to reduce the impact of interference: time spacing. In a study by Underwood & Ekstrand (1967):

- "2 groups learned A-B for 32 trials, learned A-C to one perfect recitation 3 days later, and recalled A-C after 24 hr. 2 other groups learned both lists in immediate succession followed by 24-hr, recall of A-C. 1 group from each schedule had 6 A-B pairs retained in A-C. The results showed that the 3-day separation of A-B and A-C markedly reduced proactive inhibition ..."

In other words, interference is more likely to occur when highly related pieces of knowledge are learned simultaneously or in close succession – but by spacing out these related pieces of knowledge over time, a teacher can mitigate the effects of interference. This strategy is called non-interference.

What’s more, non-interference also helps keep learning tasks varied and exciting for students. Learning can feel like a grind when you are made to focus on the same types of concepts and problems for a long time, just like exercising can feel like a grind if the entire workout consists of a single exercise (especially if it’s one of your least favorite exercises). Just like a personal trainer packs a wide variety of exercises into each workout to maintain motivation, teachers leveraging non-interference pack a wide variety of topics into each learning session to keep things exciting.

References

Campbell, J. I. (1987). The role of associative interference in learning and retrieving arithmetic facts. Cognitive processes in mathematics, 107-122.

Underwood, B. J., & Ekstrand, B. R. (1967). Studies of distributed practice: XXIV. Differentiation and proactive inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(4p1), 574.

This post is part of the book The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Jan 2024). Suggested citation: Skycak, J., advised by Roberts, J. (2024). Cognitive Science of Learning: Minimizing Associative Interference. In The Math Academy Way (Working Draft, Jan 2024). https://justinmath.com/cognitive-science-of-learning-minimizing-associative-interference/

Want to get notified about new posts? Join the mailing list and follow on X/Twitter.